The myth of human progress is one of the most resilient and pervasive beliefs of the modern time. Early versions of this myth could be seen hundreds of years ago. Herbert Spencer was a Victorian era sociologist who applied the principles of evolution to society. He taught that “the belief in human perfectibility merely amounts to a belief that, in virtue of this process, man will eventually become completely suited to his mode of life.”[1] The process of evolution, according to Spencer, must end with humanity being ultimately evolved, progressing to a point where they are perfected. After bringing the United States into the First World War because “the world must be made safe for democracy”[2] President Woodrow Wilson lobbied for the creation of the League of Nations believing that a peaceful community of nations could usher in a utopian society.[3] History has shown the naiveté that the League of Nations represented, with disastrous results. Even pop culture believed that the general motion of humanity was upward. In the song, Right Here, Right Now by Jesus Jones, released in 1990, ironically on September 11, the British pop band expresses joy at the apparent revolutionary evolution of mankind. “I was alive and I waited for this/ Right here, right now/ There is no other place I want to be/ Watching the world wake up from history”.[4] In the 2016 presidential cycle, President Trump won based largely on the sentiment that if elected he will “bring [America] back bigger and better and stronger than ever before, and we will make America great again.”[5] From progressive Social Darwinists, to British dance bands, to Presidents, the belief that things are destined to get better is deeply ingrained in society.

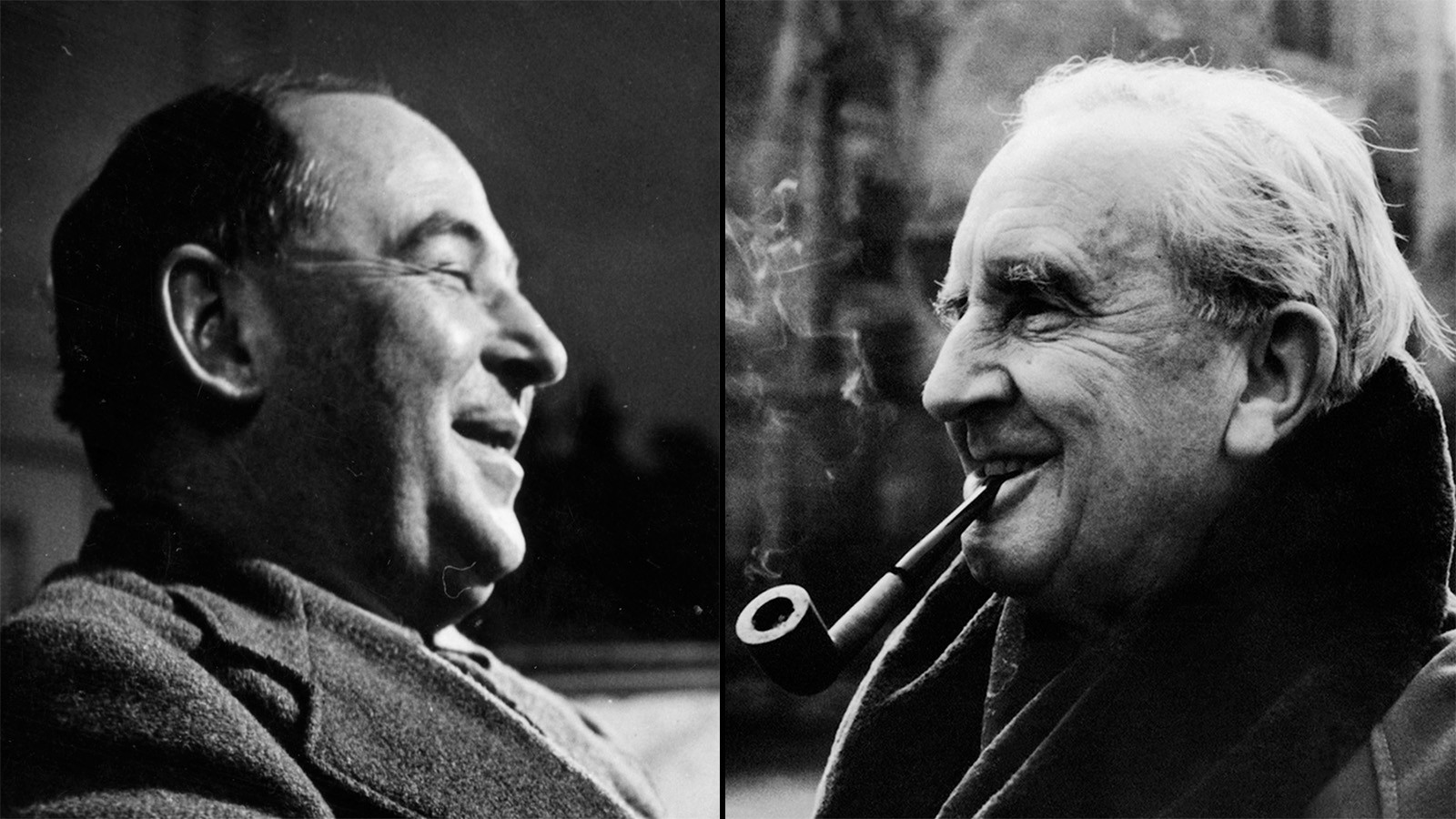

However, Both Lewis and Tolkien seem to be critical of this idea of the inexorable upward evolution of mankind. Instead, they appear to believe in a general winding down of history; a slow movement away from bliss to destruction. In this paper, I will compare their writings in a few major areas. First, I will look at how they describe the overall pristine nature of the world in their creation myths. Then I will examine the belief that their characters have in a better or more glorious past or the distrust of progress away from the past that exists in their stories. I will next examine how the idea of the general winding down of history is presented in their works dealing with eschatology. Finally, I will show that even though the means will not be human progress, there is a final hope offered by both authors.

In Tolkien’s sub-creation of Middle Earth, the creation of Arda is certainly tumultuous and obstructed at many turns by Melkor, yet it is a place of bliss. “Then Melkor saw what was done, and that the Valar walked upon Earth as powers visible, clad in the raiment of the World, and were lovely and glorious to see, and blissful, and that the Earth was becoming as a garden for their delight, for its turmoils were subdued.”[6] The imagery projected by Tolkien in this section is Edenic. Earth was a delightful garden full of beauty and bliss. The Noldor were also in a near pristine state early in the Silmarillion. “Great became their knowledge and their skill; yet even greater was their thirst for more knowledge, and in many things they soon surpassed their teachers. They were changeful in speech, for they had great love of words, and sought ever to find names more fit for all things that they knew or imagined.”[7] Not only is early Arda Edenic in its geography, but knowledge and wisdom are shown to be highly developed. A love of language was present in the Noldor and they were coming up with more glorious ways of describing the creation around them. Alternate versions of Middle-Earth in Tolkien’s other works share this same sense of an unspoiled Arda. One passage in The Lost Road encapsulates Tolkien’s conception of Middle-Earth. “The Father made the World for Elves and Mortals, and he gave it unto the hands of the Lords. They are in the West. They are Holy, blessed, and beloved: save the dark one. He is fallen. Melko has gone from Earth: it is good. For Elves they made the Moon, but for Men the red Sun; which are beautiful. To all they gave in measure the gifts of Ilúvatar. The World is fair, the sky, the seas, the earth, and all that is in them. Lovely is Númenor.”[8]

Lewis’s country of Narnia was much the same way at the time of its creation. When the reader experiences the creation of Narnia in The Magician’s Nephew, they are presented with a glorious, pristine land. Even the act of creation itself was lovely. “But it was, beyond comparison, the most beautiful noise he had ever heard. It was so beautiful he could hardly bear it.”[9] Narnia was not some chaotic, primordial soup. It was breathtakingly beautiful in its very creation. Although, like Arda, Narnia was stained almost from the beginning by the introduction of the witch, it was still a place of bliss. The descriptions used by Lewis are beautiful and portray the sublime. “They stood on cool, green grass, sprinkled with daisies and buttercups. A little way off, along the river bank, willows were growing. On the other side tangles of flowering currant, lilac, wild rose, and rhododendron closed them in.”[10] Narnia was idyllic. Even the antagonist, Uncle Andrew, realized the power and unspoiled nature of Narnia. “I shouldn’t be surprised if I never grew a day older in this country! Stupendous! The land of youth!”[11] In one of the most humorous passages of the book, the creatures of newly formed Narnia did not even have a concept of evil. After hearing Aslan exclaim that an evil had entered the world, the creatures are terribly confused. “The others began talking, saying things like ‘What did he say had entered the world? – A Neevil – What’s a Neevil? – No, he didn’t say a Neevil, he said a weevil – Well what’s that?’”[12]

The intentionally Edenic description of the planet Perelandra takes the better part of several chapters to unfold. The clearest way to show its pristine nature is to examine the passage where death first enters the world. Ransom comes across a frog that has been mutilated by Weston, the un-man. “On earth it would have been merely a nasty sight, but up to this moment Ransom had as yet seen nothing dead or spoiled in Perelandra, and it was like a blow in the face.”[13] Lewis continues a few sentences later. “The thing was an intolerable obscenity which afflicted him with shame. It would have been better, or so he thought at that moment, for the whole universe never to have existed than for this one thing to have happened.”[14] The beauty and unsullied nature of Perelandra was so overpowering that the mutilation of this small creature is beyond comprehension to Ransom.

In these three examples the created world is described as a place of bliss and a place of wonder. Their sub-created worlds were nearly perfect at the beginning. There was no need in these worlds for progressive humanity to come and mechanize it to greatness. Technology, science, and social reform was not going to cause any improvement in the human condition in these worlds. The progression was not upward to a golden age. Indeed, from their creation the general direction of these worlds was downward.

This downward movement is also evidenced by the characters in the stories longing for a more glorious past, or if not explicitly longing for the past, treating those who came before with honor and respect and viewing them as higher. Elrond speaks to this more glorious past and laments the current state of affairs when he recounts a brief history of Middle-earth in the Council of Elrond. Speaking of the glories of the past he states “Never again shall there be any such league of Elves and Men; for Men multiply and the Firstborn decrease, and the two kindreds are estranged. And ever since that day the race of Númenor has decayed, and the span of their years has lessened.”[15] Elrond speaks of decay and of his belief that things will never reach the former glory of the past. He adds emphasis to this point by continuing “But in the wearing of the swift years of Middle-earth the line of Meneldil son of Anárion failed, and the Tree withered, and the blood of the Númenorians became mingled with that of lesser men.”[16] Elrond uses words that add to his theme of decay; wearing down, withering, and blood lines being watered down. The sorrow of the Elves is present in his speech.

Later in the story Faramir expresses this sentiment in several ways while sharing stories with Sam and Frodo. “Yet even so it was Gondor that brought about its own decay, falling by degrees into dotage, and thinking that the Enemy was asleep, who was only banished not destroyed.”[17] Like Elrond, Faramir uses the language of decay to talk about what happens to humans over time. He speaks of the High Men of the West and laments that his people had become “Middle Men, of the twilight, but with memory of other things.”[18] The people of Gondor no longer have the same position of the people of old. Faramir makes this point by showing how the High have fallen to the Middle, and that they are in the twilight. This exchange is more evidence that Tolkien’s characters believed the general flow of history to be a downward progression. Completely absent in the mind of Faramir is the myth of progress. He had a sober understanding that the flow of history was one ending in nightfall, and he believed them to be in the twilight of that day already.

The characters in the world of Narnia have a similar respect for history. There is a reverence in the tone used by the unicorn, Jewel, to describe the peaceful years of Narnia was reverent.[19] Both Jewel and Tirian have a regard for those who came before and the rule of the High Kings and Queens of Narnia. Tirian maintained such respect that he called out to Aslan for their help in his time of need.[20]

In addition to the reverence for the high past that exists in Narnian leadership, there is also a distrust of the concept of progress on the part of King Caspian; particularly that type of progress which utilizes charts and graphs and pretends to be for the economic good or what is referred to as development. “’But that would be putting the clock back,’ gasped the Governor. ‘Have you no idea of progress, of development?’ ‘I have seen both in an egg,’ said Caspian. ‘We call it Going bad in Narnia. This trade must stop.’”[21] Lewis uses to character of Caspian to lay bare the essence of those who claim progress and development are the ultimate ends. The governor was under the mistaken impression that progress and economic development was the chief purpose of managing the island. Caspian cuts through all the pretenses and calls it what it is – going bad.

Perhaps nowhere in their fiction to Lewis and Tolkien refute the myth of progress than in their sub-creation’s passages dealing with death and eschatology. Much can be learned from Appendix A of The Lord of the Rings. After Aragorn laid down in the House of the Kings, we read this description of his visage. “And long there he lay, an image of the splendor of the Kings of Men in glory undimmed before the breaking of the world.”[22] One of the simple implications of this passage is that the world will be broken. This is easy to pass over, but I believe it is important. It shows that the progression of Middle-earth is toward brokenness. This is a movement away from the initial bliss of Arda; more evidence that Tolkien did not believe in the general upward progressions of humanity toward a utopian ideal. The use of language in the passage describing the passing of Arwen also casts a forlorn shadow. “But Arwen went forth from the House, and the light of her eyes was quenched, and it seemed to her people that she had become cold and grey as nightfall in winter that comes without a star. Then she said farewell to Eldarion, and to her daughters and to all whom she had loved; and she went out from the city of Minas Tirith and passed away to the land of Lórien, and dwelt there alone under the fading trees until winter came. Galadriel had passed away and Celeborn also was gone, and the land was silent.”[23] The language is evocative and melancholy. Light is quenched, the nightfall is cold and grey, she was alone. Both Galadriel and Celeborn were gone, and the land was silent. Again, the language used here by Tolkien is showing a winding down; a move from the greater to the lesser.

This transition is even more stark in Lewis’s depiction of night falling in Narnia in The Last Battle. The entire tone of the book is much darker than any of the other Narnia adventures. The people in Narnia have largely forgotten Aslan’s true nature, and are fooled by a donkey in a dead lion’s skin. The fall of Narnia is clearly stated in the words of Farsight the eagle.

“’Two sights have I seen,” said Farsight. ‘One was Cair Paravel filled with dead Narnians and living Calormenes: the Tisrocs banner advanced upon your royal battlements: and your subjects flying from the city – this way and that, into the woods. Twenty great ships of Calormen put in there in the dark of the night before last night.’ No one could speak. ‘And the other sight, five leagues nearer than Cair Paravel, was Roonwit the Centaur lying dead with a Calormene arrow in his side. I was with him in his last hour and he gave me this message to your Majesty: to remember that all worlds draw to an end and that noble death is a treasure which no one is too poor to buy.’ ‘So,’ said the King, after a long silence, ‘Narnia is no more.’”[24]

Not only was Narnia finished as a political entity at this point, the words of Roonwit imply that the world itself was drawing to an end. That is certainly the feeling cast by the whole book. The ending is more explicit a few chapters later in “Night Falls on Narnia.” The un-creation in many ways mirrors the creation of Narnia witnessed in The Magician’s Nephew. It was the musical song of Aslan that was the efficient cause of the creation of Narnia.[25] It is the haunting sound of Father Time’s trumped that set into motion the un-creation. “Then the great giant raised a horn to his mouth. They could see this by the change of the black shape he made against the stars. After that – quite a bit later, because sound travels so slowly – they heard the sound of the horn: high and terrible, yet of a strange deadly beauty.”[26] The first thing to be created in Narnia was the stars. “One moment there had been nothing but darkness; next moment a thousand, thousand points of light leaped out – single stars, constellations, and planets, brighter and bigger than any in our world.”[27] The stars are the first thing to be called home in the un-creation. “With a thrill of wonder (and there was some terror in it too) they all suddenly realized what was happening. The spreading blackness was not a could at all: it was simply emptiness. The black part of the sky was the part in which there were no stars left. All of the stars were falling: Aslan had called them home.”[28] In primordial Narnia there had been nothingness in the sky and then suddenly Aslan called the stars into being. At the end, the nothingness begins to return, for Aslan had called them back. Aslan had created the talking beasts at the beginning and left them with a warning that they could one day return to being dumb animals.[29] We see this warning come to fruition at the end of Narnia. “You could see that they suddenly ceased to be Talking Beasts. They were just ordinary animals.”[30] Narnia was clothed with vegetation by Aslan’s song at the creation[31], and at the end it was made naked as the Dragons and Giant Lizards tore up the trees and returned Narnia to barren rock.[32] This was a world that was destined to end. Father Time had been sleeping, waiting to fulfill that very purpose. The end of the world makes clear that Lewis did not intend to tell a story of the triumph of modern man over nature. These stories blatantly refute the myth of progress. They instead clearly show the winding down of time. In Arda, it is done through forlorn imagery of a cold winter evening, and in Narnia it is an explicit winding down of history and an un-creation that mirrored the creation itself.

Considering their rejection of the myth of progress, are Tolkien and Lewis fatalists? Do they leave their readers without hope for the future? Not at all. In fact, the vision they present to the reader far surpasses any pseudo-utopia that humanity could ever devise. In the conversation between Finrod and Andreth, Finrod comes to the realization that they have reason to hope that Arda would be healed. “For that Arda Healed shall not be Arda unmarred, but a third thing and a greater; and yet the same.”[33] Finrod realizes that the Valar had not heard the end of the music of Eru. Andreth shares the hope of old with Finrod. “’They say,’ answered Andreth: ‘they say that the One will himself enter into Arda, and heal Men and all the Marring from the beginning to the end.’”[34] Tolkien is speaking here of the incarnation of Christ, who will make all things new. This is, in my opinion, the most clear vision of the Christian gospel that Tolkien put into his fiction. God, or Eru, will enter Arda and make all things new. Note the similarities between the passage presented in Athrabeth and the Biblical account of the New Heaven and the New Earth. First from the Athrabeth: “And then suddenly I beheld as a vision Arda Remade; and there the Eldar completed but not ended could abide in the present for ever, and there walk, maybe, with the Children of Men, their deliverers, and sing to them such songs as, even in the Bliss beyond bliss, should make the green valleys ring and the everlasting mountain-tops to throb like harps.”[35] Compare to the Biblical account from Revelation 21. “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ‘Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God. He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away.’”[36] In Tolkien’s legendarium, as in the Christian religion, God himself will come into the world and heal all the hurts. This is not the result of the progress of man. It is the work of God himself.

Lewis view is similar, and harmonizes nicely with that of Tolkien. The hope that Lewis offers is that the world in which we live is a shadow of the true world. The things that we hold dear in the present world are dear to us because they “remind” us of the true things. The Unicorn in The Last Battle sums this up perfectly. “I have come home at last! This is my real country! I belong here. This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now. The reason why we loved the old Narnia is because it sometimes looked a little like this.”[37] Lewis echoes a different passage of Scripture in his writing. The author of Hebrews says in the 9th chapter, “For Christ has entered, not into holy places made with hands, which are copies of the true things, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf.”[38] The things on earth are in some sense copies of a truer reality. The idea that humanity could use the tools of “progress” to make the copy better than the true reality is foreign to Lewis. The true hope, the true progress of man is the progress we make further up and further in to Aslan’s country. Night had fallen upon Narnia, yet there was hope. “The term is over: the holidays have begun. The dream is ended: this is the morning.”[39] The hope the reader is left with is not the false hope given by the prophets of the myth of progress. The hope is in entering the true world and leaving the Shadow-Lands. Indeed, “All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story, which no one on earth has read: which goes on forever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.”[40]

Both Lewis and Tolkien offer their readers ultimate hope. It is not a humanistic hope based in the power of technology and science to bring the human race into bliss. They offer a deeper hope, founded on the very presence of God; a God who enters into his creation to right the wrongs and give us a world restored, a God who ushers us into the ultimate reality of which current life is just a shadow. We can, along with Lewis and Tolkien, place our hands on the shoulder of Sam Gamgee and say “yes, everything sad is going to come untrue.”

[1] Spencer, Herbert. Social statics, or, The conditions essential to human happiness specified, and the first of them developed. Place of publication not identified: Nabu Press, 2010. [The Evanescence of Evil Part 1, Chapter 2]

[2] Wilson, Woodrow. Sixty-Fifth Congress, 1 Session, Senate Document No. 5

[3] Christian, Tomuschat. The United Nations at Age Fifty: A Legal Perspective. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1995. [77]

[4] Edwards, Mike. Doubt. Jesus Jones. SBK Records. CD. 1990.

[5] “Donald Trump’s Presidential Announcement Speech.” Time. Accessed March 28, 2017. http://time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/.

[6] Tolkien, J. R. R., and Christopher Tolkien. The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001. [21]

[7] Ibid, [60]

[8] Tolkien, J.R.R, and Christopher Tolkien. The Lost Road and Other Writings: Language and Legend before The Lord of the Rings. New York: Ballantine Books, 1996. [79]

[9] Lewis, C.S. The Magician’s Nephew. New York. Scholastic Inc. 1988. [99]

[10] Ibid. [107]

[11] Ibid. [112]

[12] Ibid [119-120]

[13] Lewis, C. S. Space Trilogy. Perelandra. New York: Scribner Paperback Fiction, 1996. [108]

[14] Ibid. [109]

[15] Tolkien, John R.R. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006. [238]

[16] Ibid. [238]

[17] Ibid. [662]

[18] Ibid. [663]

[19] Lewis, C.S. The Last Battle. New York. Scholastic Inc. 1988. [88-89]

[20] Ibid. [32]

[21] Lewis, C.S. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. New York. Scholastic Inc. 1988. [49]

[22] Tolkien, The lord of the rings. [1038]

[23] Ibid. [1038]

[24] Lewis, The Last Battle. New York. Scholastic Inc. 1988. [91]

[25] Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew. [107]

[26] Lewis, The Last Battle. [150]

[27] Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew. [99]

[28] Lewis, The Last Battle. [151]

[29] Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew. [118]

[30] Lewis, The Last Battle. [153]

[31] Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew. [104]

[32] Lewis, The Last Battle. [155]

[33] Tolkien, J.R.R. The Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth. The Thain’s Book. Accessed March 25, 2017. https://thainsbook.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/athrabeth.pdf. [21]

[34] Ibid. [24-25]

[35] Ibid. [22]

[36] The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. ESV® Permanent Text Edition® (2016). Copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

[37] Lewis, The Last Battle. [171]

[38] The Holy Bible, ESV. [Hebrews 9:24]

[39] Lewis, The Last Battle. [183]

[40] Ibid. [184]