The myth of human progress is one of the most resilient and pervasive beliefs of the modern time. Early versions of this myth could be seen hundreds of years ago. Herbert Spencer was a Victorian era sociologist who applied the principles of evolution to society. He taught that “the belief in human perfectibility merely amounts to a belief that, in virtue of this process, man will eventually become completely suited to his mode of life.”[1] The process of evolution, according to Spencer, must end with humanity being ultimately evolved, progressing to a point where they are perfected. After bringing the United States into the First World War because “the world must be made safe for democracy”[2] President Woodrow Wilson lobbied for the creation of the League of Nations believing that a peaceful community of nations could usher in a utopian society.[3] History has shown the naiveté that the League of Nations represented, with disastrous results. Even pop culture believed that the general motion of humanity was upward. In the song, Right Here, Right Now by Jesus Jones, released in 1990, ironically on September 11, the British pop band expresses joy at the apparent revolutionary evolution of mankind. “I was alive and I waited for this/ Right here, right now/ There is no other place I want to be/ Watching the world wake up from history”.[4] In the 2016 presidential cycle, President Trump won based largely on the sentiment that if elected he will “bring [America] back bigger and better and stronger than ever before, and we will make America great again.”[5] From progressive Social Darwinists, to British dance bands, to Presidents, the belief that things are destined to get better is deeply ingrained in society. Continue reading “Fighting the Long Defeat”

Of Homely Houses and Dangerous Dwellings

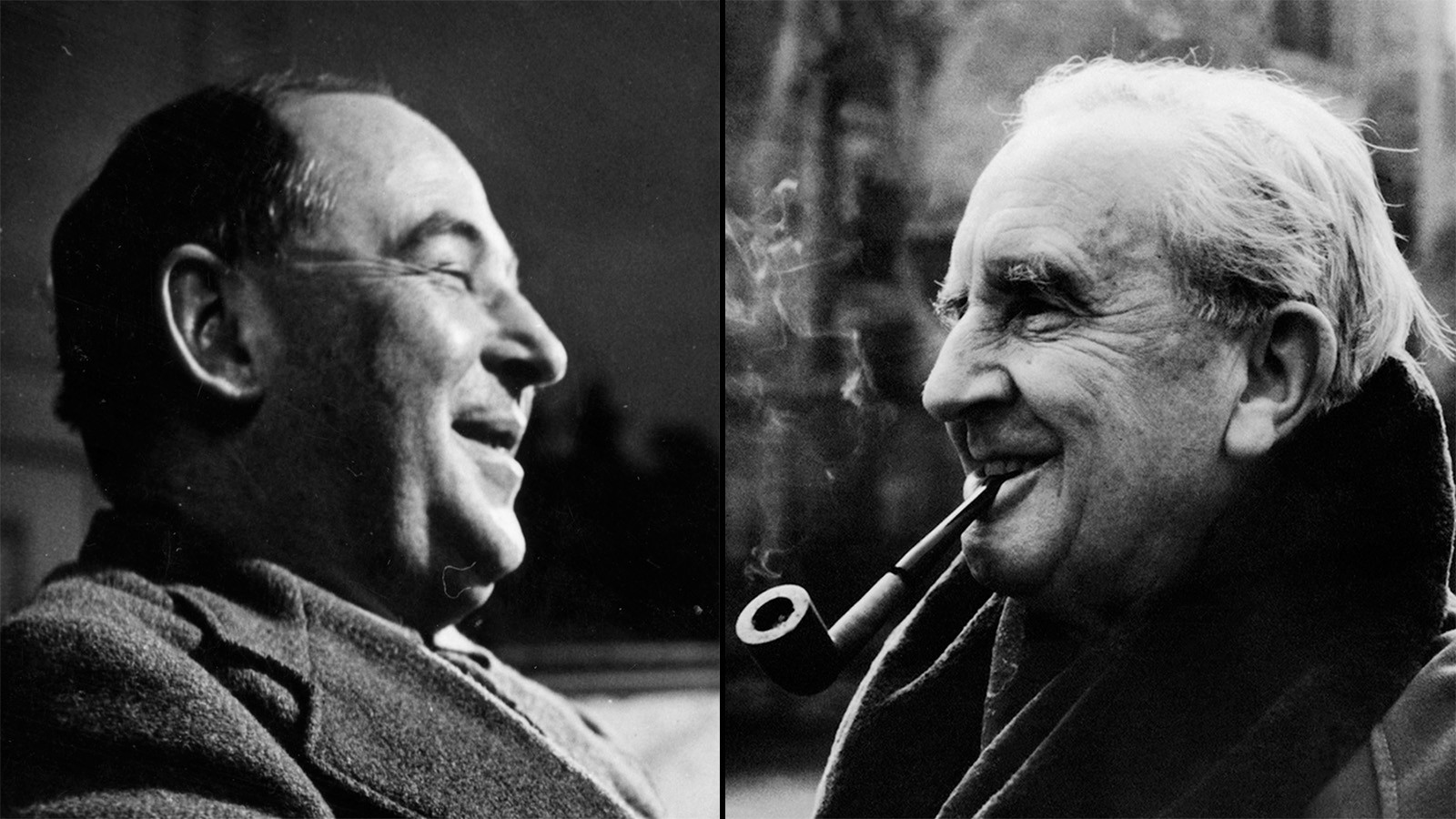

An unsuspecting hobbit is minding his own business, smoking his pipe while standing outside on a glorious morning when an unexpected wizard in a blue hat arrives and sets in motion a fantastic and perilous adventure. A curious little girl and her siblings are exploring a stately English country home when she stumbles through the coats in a wardrobe and finds herself in a magical world of talking animals and terrible dangers. In the first few pages of The Hobbit and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe the reader is presented with both the familiar and the fantastic. Tolkien and Lewis both do a masterful job in these stories of weaving the mundane and the magnificent together in compelling ways. Continue reading “Of Homely Houses and Dangerous Dwellings”

C.S. Lewis on Telling Stories

A love of stories is knitted into the fabric of humanity. Storytelling transcends cultures and epochs. Bedtime stories are told to breathless children waiting to hear what comes next. Scary stories are told in hushed tones around camp fires in the woods. Love stories are told by poets to star crossed lovers. War stories are told by veterans to their grandchildren. With stories being ubiquitous, it seems odd that so few people stop to ask “what exactly is a story?” A similar thought troubled C. S. Lewis enough that he wrote an essay, “On Stories” which examines the definition of a story and ruminates on what makes a story good. Towards the end of the essay, Lewis distills his premise into the following two sentences. “To be stories at all they must be a series of events: but it must be understood that this series—the plot, as we call it—is only really a net whereby to catch something else. The real theme may be, and perhaps usually is, something that has no sequence in it, something other than a process and much more like a state or quality. Giantship, otherness, the desolation of space, are examples that have crossed our path” (17). In Out of the Silent Planet, it is as if Lewis gives the reader an object lesson in how he believes one should approach the art of storytelling. For Lewis, there needs to be more than excitement for excitement’s sake. There needs to be a pleasure that comes from deep imagination, from experiencing a sense of “otherness.” While Lewis describes several examples of this in his essay that are also demonstrated in Out of the Silent Planet, I will focus on three that the book exemplifies particularly well. Continue reading “C.S. Lewis on Telling Stories”